|

HANDBALL PLAYERS, CONEY ISLAND (2002, oil on canvas, 28x26cms) by permission of Max Ferguson

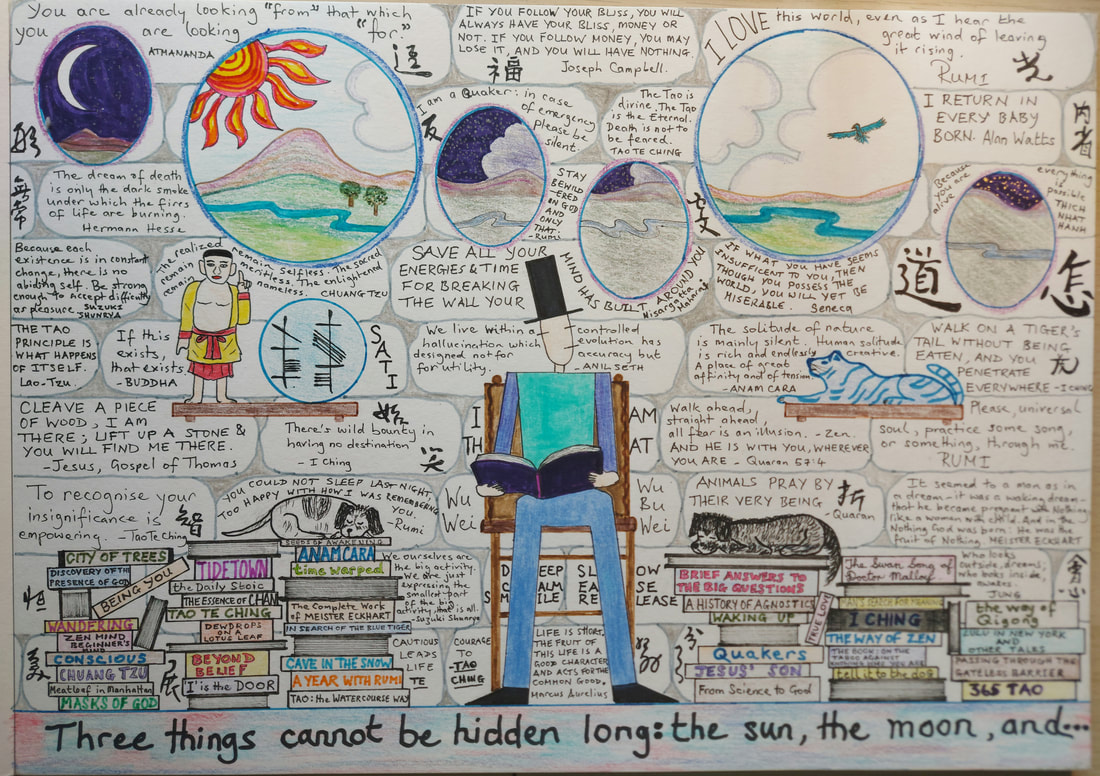

Who knows? A gang thing? Some crazy random guy? A loner? Just one shot. That’s all it was. Hit Dyson right in the temple. He dropped like a sack. With the ball in his hand. Still tight in his grip as he lay on the ground. When they told his grandmother, who’s raised him since he was a baby, she wailed. She howled and beat the sides of her head with her fists. How? How? She screamed. No, no, she cried. Why … why … a good Christian boy … please Jesus, Mother of God, please no. It should never have happened. He wasn’t into handball. Basketball was his game. In fact, basketball was pretty much his life. It was only because Tyrone said that Marlene watched the boys play handball that he decided to join in. To show some skills. For he’d a real thing for Marlene, ever since third grade. To seal the deal he’d heard she’d broken with Jackson, what with his brother and the pending meth charge and her old man warning her off. So, maybe he’d be in with a chance. Maybe even lose his virginity before school breaks up for the summer. Now there was something to dream on. Almost as exciting as his basketball scholarship to Missouri that he’d be hearing about on the twenty-fifth of next month. Sometimes, at night, he’d weigh up what he’d want more. His first real sex before the summer school break? Or the basketball scholarship? Both please, Jesus (and if it could be Marlene for one and Missouri for the other, that’d be just perfect). Just before the bullet, just before it all came crashing down, Dyson played a great shot, looked up at Marlene and she gave him the look he’d been waiting for, waiting for all his short life. Kids from his school pinned messages and ribbons, flowers and keepsakes to the fencing of the handball court. The following Saturday a rally took place along Surf Avenue to protest at all the violence in the area and to demand an end to the drug dealing. No one was ever convicted of Dyson’s murder and no one responded to the call for witnesses. Maybe it was just a random act of violence in a world where violence is so often calculated and targeted. But it’s endlessly strange how life has a habit of turning out. Like Jose Mendes Junior, from Camden, New Jersey, who if events had turned out otherwise would have joined his uncle’s garage business and given up on his dreams. Instead he took up a basketball scholarship to Missouri, officially vacated by a boy who, “due to unforeseen circumstances was unable to enrol”. The day before he left home, Jose's grandmother, with tears of joy in her eyes, baked a milk cake to celebrate the first Mendes ever to make it to college. Back on Coney Island, Dyson’s grandmother cried herself to sleep, just as she would do every night for the rest of her life. Pageant Books (oil on panel, 30 x 30cms), 2009, with permission of the artist, Max Ferguson.

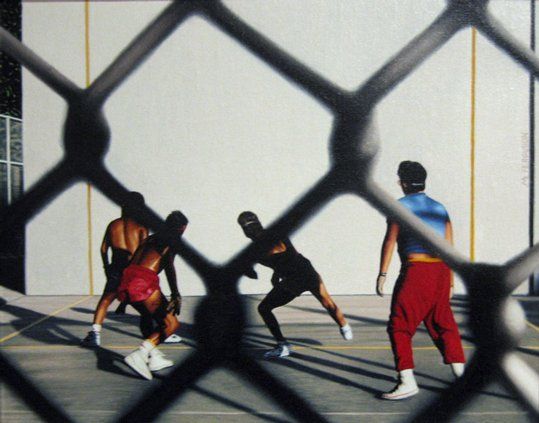

This could just as well be a history lesson. This library, an ancient relic. A museum. A mausoleum of brittle pages. Such are the thoughts of David Thompson, the school’s librarian as he gathers himself to address the class. He turns on the slide projector. The one he keeps in the cupboard. Part of his private war against “new technology”. When, forty years ago, he’d raised funds to bring the machine to the school (with its fifty-slide capacity carousel and its remote control) he was deemed an innovator. Now the children (and staff, behind closed doors) mock this dinosaur in their midst. This ancient wizened man who bans Smart Phones and IPads from the library. Who allows books to pile up on shelves. Out of order. The Principal, a kindly, not unsympathetic man, has indulged Thompson’s war of the words. But soon the librarian will be gone. Retired. Canute with no more tides to push against. To be replaced by a media resources officer. Where a love of books will not be an essential qualification for the position. ‘Settle, children,’ he says as he turns out the light. The carousel rotates and clicks at his bidding. A picture appears on the screen. Amplified. He waits. The hum of the projector, the darkened room, the single beam and singular image quietening the class. ‘What do you see?’ he asks. ‘… … …’ ‘… … …’ ‘Celia … tells us what you see?’ Celia is a sensitive twelve year-old, whose mother is a potter and bright spark in the idling engine of this small Midwest town. ‘A woman … in a bookshop. Looking for something … in the book she’s holding.’ ‘… … …’ ‘Maybe it’s the wrong book,’ says Raymond, whose father, now unemployed, was the manager of the town’s only bookshop until it closed nine months ago. Charlie Howson (who never speaks), who wishes he’d a different name, who wishes he didn’t have pimples, who wishes he didn’t have to hide behind his fringe, who wishes his father wasn’t a drunk, who wishes his brother wasn’t in juvenile detention, hears the sounds of the teacher, the murmurings of his classmates. But it’s the voice in his head that commands his attention. I’d be tall and handsome. I’d be sitting at the table sorting through the jumble of books. I’d own the bookshop. I’d ask the woman what she was looking for. In her fine coat. Her straight blond hair. She’d look at me. She’d say the name of a book. I’d know it, for this is my bookshop. She’d be impressed by me. I’d find the book she is looking for. She’d smile. She’d be happy. She’d let me hold her hand. She’d let me love her. David Thompson turns off the projector. Switches on the light. He looks out at the class of faces. His life’s work nearly over. And, like in every classroom, he thinks the thoughts of every teacher. Have I ever made a difference? Ever touched a heart? The buzzer sounds. The children stir, waiting to be dismissed. Woman in Cafe (oil on panel, 30 x 30 cm) 2009

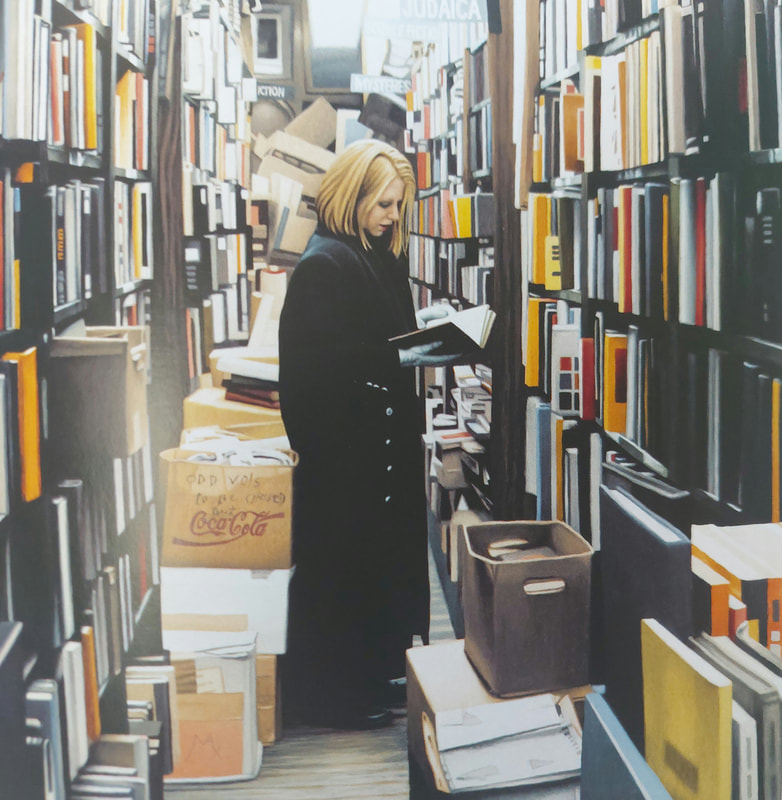

No time now to finish the cake, or to order a second cup of coffee. She must move on. And quick. There it is; on page five. All the little details. The police had arrived at her apartment next to the Silver Bullet Bar, off Washington Street, Champaign, Illinois. “It is quite clear that those in attendance appear to have left in great haste. The television set was still on and a tap was running in the sink.” Officer Brandon was reported as saying. “We are especially interested in questioning Ms Hang who had recently taken a lease on the property and appears to have been the occupant. She was last seen drinking in a nearby bar, but no one knows where she is now. But we urge any witnesses to come forward.” She reads on, keeping her head down. Last night, in the motel, she’d cut her hair, even thought of dying it, but decided not to. An Asian with anything but dark hair might draw attention. And attention was the last thing she wants right now. She thinks of Janet Leigh at the traffic lights. And the Bates Motel. But she no longer has a mother to run to. Nowhere to go. Nowhere to hide. Instead of colouring her hair she bought a hat that she could pull down to shield her eyes. As she does now. Looking around to see if anyone seems to be noticing her. If anyone else is reading the paper. The news. There in the middle of the page is her photo, with her parents. It was taken at their lakeside house, two summers ago. “Who would have thought such a terrible thing could happen,” she reads, hearing the sound of the janitor’s voice in her head. “Such a quiet, polite girl. Always said good morning and smiled. She was studying at the university. A very studious girl. Never caused any trouble. Parties or that sort of thing.” In the following paragraph the reporter describes the scene. She finds it hard to focus on the words. Enough is enough. More than enough. She folds the paper, tugs on the front of her hat and stands up to leave. There, right in front of her, is the waiter. He looks concerned, surprised. ‘Everything alright, Miss? … Something wrong with the cake?’ ‘No … no,’ she says, startled; the strange way he seems to be looking at her. ‘It’s me … I mean … it’s not the cake … I just have to go now,’ all but pushing past him, dropping the paper, reaching to pick it up, then thinking better of it. ‘… it’s alright. Leave it … on the floor … I have to go … now.’ The waiter watches her hurry through the open door and then, through the café window, sees her fumbling with the keys to the white saloon car parked directly outside. Carefully balancing his tray of dirty plates and cutlery he bends down and picks up the pages of the newspaper that lie splayed open before him. Taxi Driver, 2005 (oil on panel, 15 x 23 cms) by permission of the artist, Max Ferguson.

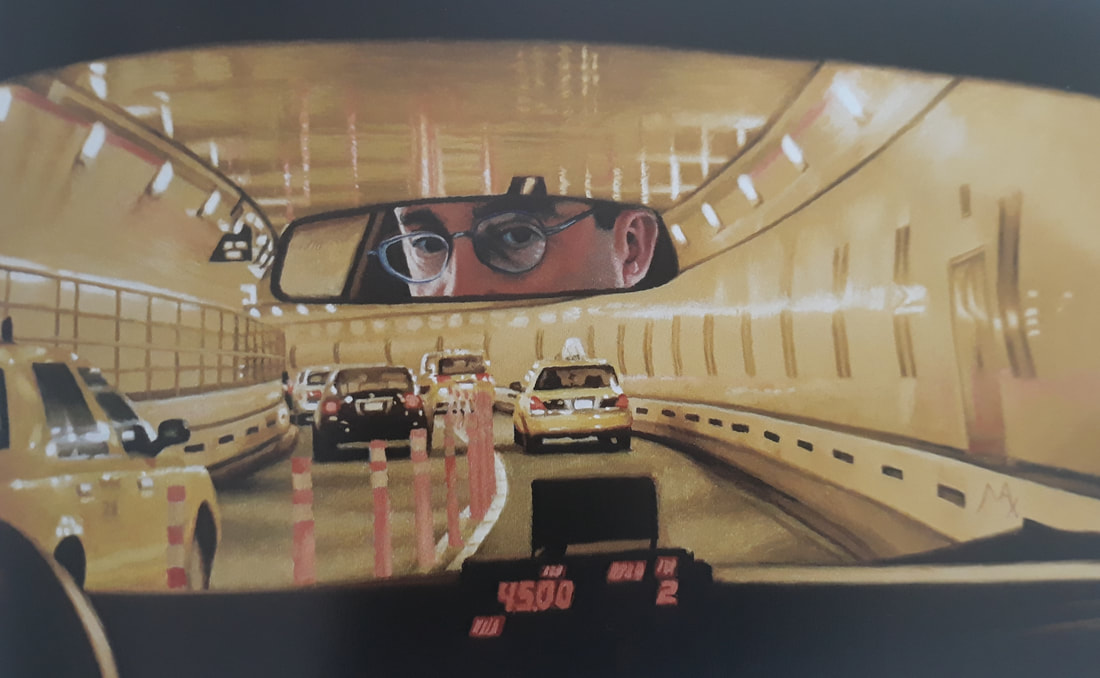

‘He’s changed lanes!’ ‘It’s okay. Trust me. I’m all over it. If he takes the filter to the airport then so can we. Once we get through this tunnel.’ ‘Don’t lose him.’ ‘Take it easy. I won’t lose him. I’ve got this under control. Just relax.’ Looking in the rear view mirror I don’t like what I see. He’s sweating. Dabbing his forehead with his handkerchief. He’s panting. His eyes are bulging. Bloodshot. Maybe I should’ve heeded to my instinct after all. I had a bad feeling as soon as he banged on the window, with his “follow that car … the black one,” waving two hundred dollar bills at my face “whatever it costs … but go now!” Pointing at the black car waiting for the lights, fifty yards up the road. Pulling on the back passenger seat door handle that I’d locked against all the Brooklyn crazies. You get a sixth sense in this job. I’m sure it’s the same in other lines of work. But for me it’s a feeling in the back of my neck. Like some kind of danger barometer. When I wound down the window to this guy the needle began to jump. It wasn’t just his body language: the agitation, the high anxiety. Or the pitch, tone and tempo of his voice. Something else altogether. What the hell I thought. It’d been a bad week. The fuel pump had finally blown, so I’d had no work Wednesday and a two-hundred-and-eighty dollar garage bill. Today I’d waited two hours at JFK for a thirteen dollar job. The luck of the draw they say; but that made three unlucky airport draws in a row. To top it off I get a call from Maxine while I’m waiting at the taxi-rank telling me if I miss another childcare payment I’d be hearing from her lawyer. My ear was still buzzing from her abuse when I get the bang on the window. Driving along I keep a careful eye on him. And a third eye on the black car. And another eye on the road. But I figure he needs me and so long as the black car stays on the Van Wyck Expressway it’ll work out okay. There’s an old hymn on the radio. One I recognize from church days. Then the preacher comes on. He talks about life’s journey. The stresses of the modern world. “Each one of us has a unique pathway,” he says. “Look to the scriptures. Proverbs 3:6.” A hundred yards ahead, the black car takes a sudden left off the freeway, before the airport, onto an unlit slip-road towards the cargo warehouses. ‘Turn!! Turn!!’ He’s leaning over the front seat. His breath steaming in my ear. In the mirror his face is huge and red, veins bulging in his neck, and eyes looking like something from the devil. ‘Follow that car! You! … Turn! Don’t mess with me!’ “… Seek God’s will in all you do and he will show you the path to take.” Oil on panel, 76 x 100 cm, 1984, by permission of the artist. Max Ferguson.

So you’re sorry. Sorry that you don’t love me anymore. Sorry that it’s not meant to work for us. Great timing. Your message, I mean. Five minutes before I was due on stage. You must’ve known I’d see it before I went out there. Standing in the wings. Checking the good luck texts. Even got one from your mother (“You’ve really hit the big time. I saw Joan Rivers and Lenny Bruce at The Bitter End when you and Ronny were but twinkles in an eye! Break a leg, sweetie. Love from the one who brought loverboy into your life. xx”). And there was your greeting, nestled in amongst them all. A black hole in a sparkling galaxy. I can only think your timing was deliberate. Like method acting. Like the way you’ve always said my delivery needed toning down. Less upbeat. More deadpan. Go in hard, get out early. Wasn’t that what they taught us at acting school? If you wanna be a stand-up. In hard, out early. Like you and me, eh? Full on from the beginning. To the end? But I wasn’t ever planning to get out, early or late. It seems like that’ll be you. Your plan. In this comedy imitating tragedy. But it worked. You slowed me right down. Like I was in a trance. If you want to know, the routine went over really well. I ran with the hipster café number. Started off with the gag about menus dribbled into the sawdust on the floor. Then about the new super seed that no one could pronounce except for the waiter. From Peru. And how you know it’s good for you by the length of time it sticks between your teeth. Perfect for the Village crowd. But your “sorry … I realise I don’t love you” kept rolling around the back of my mind. So. Less manic. So. More … measured … subdued. Thinking about it, maybe I should arrange for a catastrophic surprise just before every gig. Like shock therapy without the electrodes. To keep me detached. Mono-toned. To get my timing right. Yes. And then I could build it into my act. The way so many comics do who’ve just had a baby … or turned lesbian. Pooh and hairy legs. Leaking breast-milk and furry cups. That’s it. I’ll run a new routine about emotional pain as the alternative to lithium for manic-depressive stand-ups. And maybe something else (not about the baby we talked of) … but about the comic jilted on her big night. Like the small-town gladiator at the Colosseum in Rome. This funny girl from Avonmore, Pennsylvania. At The Bitter End, 147 Bleecker Street, NYC. You say by the time I get home you’ll be gone. Better that way, you said. Well the M train’s late, so there’s no hurry. They liked me. At The Bitter End. They want me to come back. I want you to come back. To me … please. Not in hard. Not out early. Not this too too bitter end. Oil on canvas, 91 x 142 cm, 2011, by permission of the artist, Max Ferguson.

Looking into each other’s eyes. Holding dear these precious moments. A reversal of sorts, in the turn of events. A name-band to tag in case of forgetfulness. If words fail. If all gets lost. And will you take away with you his watch? When the time finally comes? Your father’s watch? Will you slip it on to your wrist? When the time finally comes? His watch. That matched his pulse. The rise and the fall of the day. Marking off the seconds. The breaths. The heartbeats. That observed the small and large moments of a life well lived. Checked the minutes needed to meet the train. The walk from here to there. Well timed. Even rehearsed. Those sometime hours passed in anxious wait. For an event. A joy. A calamity. All the small and large events. Of a life well lived. That looked and said it’s time to go! the game’s about to begin! ten minutes ’til bed time! let’s not be late! we’re early! The metronome of decades, now melding into moments. Now telescoping. The house of prayer, where you stand, where you lie down. How the hands turn back and pause, returning time to the source. In a forest. A first flush of love lain out on a picnic rug. Of wool. Of taffeta. Ruffled on the dank-leaved grassy slope. The sound of water. The sense of promise. A moment to cherish. Another moment. A game of pool under a fluorescent light. Like a winter’s night. Snow in the darkened street below. The smooth special table. Like a lawn. Blue or green. The spheres, solid and weighty. A field of dreams. You two. Like communion. Like complicity. The watch. Ever present. Pacing the future. Leaving the past in its wake. The watchman, just out of view. Awaiting the allotted hour and minute and second. Patient. No soothsayer is he. More an angel. More a ferryman. The punt, still on the pond. The far shore in view. The long-stemmed oar gripped lightly. Held lightly. And, you must, when the time finally comes, with your slender fingers, gently wrest the watch from your father’s wrist. A passing away. A passing on. Taking on the mantle. Taking over the baton. When the time comes. Reverently, lovingly, you push apart the silver links of the strap; pass it over your fingers, your thumb, the meat of your hand, until it comes to rest, to home, on your own wrist. You look at it. The glass face. The simple dial. The numbers. Counting out the allotted time. Of seconds. Of days. Of years. And you observe the sinews of your arm. The back of your hand. The fingers. And you see what you’ve known all your life. All along. You stretch the muscles, the ligaments, feel the strap expand. You relax. The strap contracts. Settles. In the quiet you hear the tiny sound of time moving forward. In time honoured fashion. All fathers. All sons. The natural order. You this way. He that. Shoe Repair Shop (Oil on Panel, 16 x 16 inches, 2008) by permission of Max Ferguson.

‘Yes,’ the shoemaker says, placing the boot she’s just handed him on the counter, ‘unusual, for sure.’ But nothing more than that. He’s well used to peculiar requests, having worked in the shop, man and boy, for nigh on fifty years. ‘There was the time in the 1970s,’ he continues, as he rummages around for the pliers, ‘when a sociology professor from Columbia sent students along this street asking us to do all manner of odd things. This young kid comes into my shop, no shoes or socks. “Can you put a leather sole and heel on my bare feet?” says he.’ ‘And what did you do?’ she says. ‘I asked him how much was he prepared to pay.’ She looks a bit shocked, but his smile reflected in the mirror, reassures her. 'Ethnomethodology they called it. I like the word … ethnomethodology … it’s got a nice rhythm to it.’ ‘What?’ she says. ‘Ethnomethodology …’ he repeats, relishing the sound. ‘He told me all about it, this kid. You try to disrupt the everyday world. To see how people react. Mr. Tang in the dry cleaners next door. His student came in with a muddy cabbage and asked him to clean it. That kind of thing. But I told my student there wasn’t much you’d describe as an everyday world around here. It’s getting disrupted all the time.’ Then he turns, pliers in hand, and examines the beautifully decorated boot. A surgeon about to perform the autopsy. When she first got the letter from the solicitor and then went to their offices to collect the old cowboy boot, she was intrigued. But, just like the shoemaker (and the dry-cleaner with the cabbage) she was not that surprised. Her great-uncle was a famous eccentric and she was his only surviving relative. Family stories abounded. Like the rides he used to take on the old steamers in the south, gambling away his gold. His prodigious skill on the stock exchanges. His parsimony, living like a hermit. Travelling in boxcars. A carpet bagger without a carpet. He’d appear at functions, mainly funerals. Tall and gaunt, in his ragged great-coat, grizzly beard and grizzlier greasy hair down to his shoulders. He wore a patch, just to keep one eye spare. And always the same cowboy boots, one of which the shoemaker was now wrestling with. She watches him as he begins to free the heel from the boot. The sound and sense of it reminds her of the time she had her wisdom tooth extracted. And, like a molar being released, something falls from the yawning jaw of heel and sole and clatters on to the wooden surface of the counter. The shoemaker lifts the key by the tag and hands it to her. It is cold and heavy in her palm. The string is frayed and worn and the engraving on the metal tag is faded. She squints to read it. ‘What does it say?’ he asks. ‘… Deposit Box 25 … Wells Fargo Bank … Dubois, Idaho …’ |

AuthorThoughts on upcoming events, new book ideas, and the agonies and ecstasies of the creative process. Archives

January 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed